The charts were once dominated by pornified raunch, but in an era of identity politics and empowered women, a new kind of sexuality is emerging in pop – and warming cyberspace, when Robin Thicke and Pharrell released Blurred Lines on 26 March 2013, they had no idea (or claimed not to) that it would kickstart a debate about rape culture and misogyny in pop . The outraged response to its suggestive lyrics – particularly the refrain “I know you want it” – permanently changed the standards to which pop is held, and the way in which pop itself deals with sex.

The charts were once dominated by pornified raunch, but in an era of identity politics and empowered women, a new kind of sexuality is emerging in pop – and warming cyberspace, when Robin Thicke and Pharrell released Blurred Lines on 26 March 2013, they had no idea (or claimed not to) that it would kickstart a debate about rape culture and misogyny in pop . The outraged response to its suggestive lyrics – particularly the refrain “I know you want it” – permanently changed the standards to which pop is held, and the way in which pop itself deals with sex.

That is not to say that sex has vanished from pop since the controversy. Jason Derulo and Bruno Mars are no strangers to objectification; ex-boybanders such as the former One Direction members are still breaking with their clean-cut pasts by letting you know in song exactly how much sex they’re having; while Brit awards nominee J Hus cackles in the face of good taste. In 2016, Ariana Grande released a classic of the form in the admirably brazen Side to Side, about the inability to walk straight after a long night at the coal face.

But pop’s portrayals of sexuality have been complicated – and muted – by an unusually eventful half-decade. Intimacy has been corrupted by technology and anxiety. Female artists are redefining sexuality. Would-be seducers must acknowledge conversations about consent and gender politics. Provocateurs who aren’t progressive are soon rumbled. R&B is grappling with what pleasure looks like when black bodies are under siege from police brutality and cultural fetishisation. And LGBTQ listeners are demanding more than rote heterosexual hook-ups. This immediacy is nothing new – pop has always either shaped or reflected the social and sexual mores of its era – but the outcomes are.

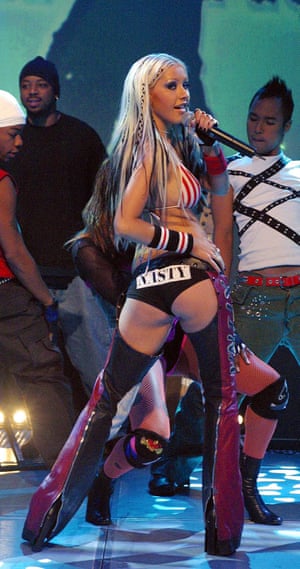

Last year, US critic Ann Powers published Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music, an inspired history of sex in pop. She writes of how rock’n’roll validated teenage desire and liberated girls; posits Robert Plant’s moan and Donna Summer’s gasps as music’s answer to the mainstreaming of pornography in the 70s; and Madonna, Prince and Michael Jackson “playing freely within the dreamscape of eroticised fantasy” as a safe outlet for sexuality during the Aids crisis. Female rap and R&B acts in the early 90s – Salt-N-Pepa, TLC – stoked a playful consciousness where safety didn’t come at the expense of pleasure. This segued, however, into the turn of the millennium and the scantily clad, raunch culture of Paris Hilton, MTV’s Spring Break and Christina Aguilera’s Dirrty. Music channels were full of pornified dance-pop videos: the likes of Eric Prydz’ Call on Me or Alex Guadino’s Destination Unknown.

If Blurred Lines had arrived during this era, nobody would have blinked, argues Vanessa Grigoriadis, author of last year’s book Blurred Lines: Rethinking Sex, Power and Consent on Campus. Instead, it parachuted into a culture where Twitter (and to a less mainstream extent, Tumblr) was enabling trenchant conversations about justice and identity. “If pop doesn’t catch up, then it’s going to find itself in the centre of a firestorm,” says Grigoriadis, “because young people today expect their idols to listen to them and what they want.”

The result, she says, is that male stars such as Chance the Rapper, Childish Gambino and Drake “are beginning to see that there is a consciousness rising among women and that they need to react to that”. This liberates them, too. “They can play with their own sexuality in a way that they couldn’t before,” says Grigoriadis, citing Drake asking in 2016’s Redemption: “Why do I want an independent woman to feel like she needs me?”

“It’s much harder for other artists to just mail it in with an overly hetero ‘bang till you drop’ song,” she says.

Ed Sheeran is far from a conventional pop Adonis, but, Powers tells me, that is what makes him a contemporary sex symbol. “Shape Of You, the biggest hit of 2017 by a long shot, is about sex. ‘Now my bedsheets smell like you’ sounds like a line from a Marvin Gaye or Joni Mitchell song.” She views Sheeran as, in some ways, the perfect Top 40 heartthrob for this era: “ He comes across as unthreatening, but he’s still sensual. In Sheeran’s song, the new couple goes out to eat, the girl eats a lot and he still wants to have sex with her. That is where anxiety about being “woke” is taking pop songwriters today.”

More significantly, listeners’ heightened awareness of pop’s gender politics began extending behind the scenes. In 2014, the singer Kesha filed a civil suit against her producer Dr Luke accusing him of sexual assault and battery. Dr Luke immediately countersued for defamation in a case that’s ongoing and Kesha’s claims were later thrown out by a judge. Regardless of the outcome, the case prompted debate about pop’s fraught power dynamics.

Justin Tranter is a leading songwriter for artists such as Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Gwen Stefani – and Kesha on her comeback album, Rainbow. He is pushing for changes. “I don’t want male writers in pop speaking for women any more,” he says. “Not only is it the right thing to do, it’s financially smart. If an artist really believes this is their story, they’re gonna sell it better.”

This understanding challenges assumptions that female pop stars have to appeal to men. Sexuality barely dents the carefree, Technicolor images of younger artists such as Norway’s Sigrid and Finland’s Alma. And while there is a utilitarian sexiness to Dua Lipa’s bikini-clad look in the video for New Rules – a massive hit in 2017 – its show of female solidarity, and relationship advice in the lyrics, are aimed firmly at women.

The way rapper Cardi B has put aside her identity as a former stripper has been key to her appeal, says Powers. “She presents herself as in control of her sexuality, but at the same time, every one of her hits focuses on her pussy. So she’s sexy, but not just sexy, and that’s seen as progress.”

Rina Sawayama is a Japanese-born, London-raised DIY pop star tipped to break out this year. Her slick sound is influenced by mainstream music from the turn of the millennium, “when labels and A&Rs were actively promoting young sexuality through acts like Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera”, she says. But that is where the similarities end. “People are more sensitive to manufactured sexuality, especially from female artists.” she says. “If singers are going to talk about sex, then it has to come from the artist; authenticity is important.” She praises the “comfy erotica” of SZA and her track Drew Barrymore: “She talks about the TV show Narcos in the first verse; it’s a perfect Netflix-and-chill song. I think it echoes how millennials – and especially people of colour – want to spend our time, in a safe space with the people we love.”

The gold standard of empowered female pop sexuality is another holdover from 2013. On Beyoncé’s self-titled surprise album, she sang with explicit command about rediscovering her sexuality after the birth of her first child. “Beyoncé boldly proposes the idea that a woman’s prime – personal, professional, and especially sexual – can occur within a stable romantic partnership,” wrote Pitchfork’s Carrie Battan.

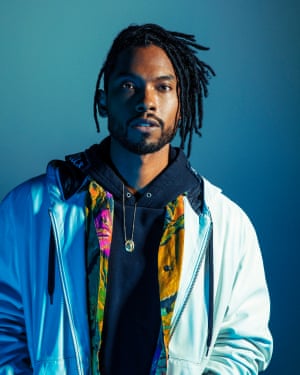

But Beyoncé’s next album represented another paradigm shift in how artists – and specifically black artists – address sexuality. Built around images of matriarchy and female solidarity, 2016’s Lemonade was assumed to confront longstanding rumours of husband Jay-Z’s affairs. “But the trauma of infidelity is about much more than matters of adulterous fucking in Lemonade,” wrote MTV News critic Doreen St Félix. “Black women in America are cheated out of spiritual and material things.” Lemonade confirmed the inseparable nature of structural injustice and interpersonal love, St Félix asserted. In the age of Black Lives Matter and an evidently racist White House, more black artists are confronting these themes. “It’s difficult to express intimacies, or make room for pleasure, when thinking about the body demands facing the many ways it can be diminished, even extinguished, instead of serving as a vessel of joy,” Powers writes. R&B star Miguel was singing straightforwardly pornographic lyrics on his 2015 album Wildheart, but last year’s War and Leisure saw sex newly intertwined with apocalypse; Beyoncé’s sister Solange’s 2016 album A Seat at the Table proposes sex as alleviation from the exhaustion of racial aggression. “I slept it away, I sexed it away,” she sings on Cranes in the Sky. “Artists like SZA, Kelela and Jhené Aiko definitely explore eroticism while also insisting on being introspective and self-reflexive in other ways,” Powers tells me. “They question the mandate for women – especially women of colour – to be sex symbols while insisting on claiming erotic agency.”

Studies state that although millennials are more fluid and open-minded about sex than previous generations, technology means they are having less sex while worrying more, a pattern reflected by pop as it abandons bravado to offer more honest accounts of anxiety and its effects on intimacy. On songwriter-turned-pop star Julia Michaels’s debut single Issues, she asks that her and her lover share their worries without judgment and “bask in the glory of all our problems”.

Rina Sawayama’s excellent single Cyber Stockholm Syndrome finds positivity in being bound with technology, celebrating a night in alone on her phone. “The way you touch just don’t feel right,” she sings. “Used to feeling things so cold, minimising windows … Happiest whenever I’m with you online.” It sounds like a future Black Mirror theme tune, but Sawayama, 27, praises the internet for enabling even the socially anxious to express themselves sexually. “I think our generation is so used to developing relationships online that it’s actually unthinkable that we can have a conversation of intimacy without mentioning social media.”

This vision of sexual sanctuary will look intolerably bleak to some. So what should erotic pop look like in 2018? Tranter, who is gay, already sees the mainstream becoming more inclusive. Last Friday, he says, gay artists Troye Sivan and Hayley Kiyoko released new singles, both co-written with LGBTQ writers, “that were clearly queer, fully humanised and sexual while still being emotional, and not fetishising – so I’m pretty hopeful.” He is currently working with black trans singer Shea Diamond, determined to present a three-dimensional portrayal of her desires. “I’m fighting my hardest to make this future come soon,” he says.

Powers, meanwhile, is keen to look beyond today’s identity-driven moment. Imagining “new bodies that are comfortable being augmented by and occupying cyberspace“, she says: “Hopefully when some equity is achieved and we can go beyond the current reckonings, people will start exploring eroticism in ways we can’t imagine.”

The Shirelles Will You Love Me Tomorrow

‘We’re all sensitive people’: five classic songs that got sex right

When Carole King and Gerry Goffin were asked to follow up the Shirelles’ Tonight’s the Night – about a girl contemplating the loss of her virginity – they simply decided to continue the narrative. Here, the girl’s anxieties that her beau may break her heart harden into a stark demand for assurance that he won’t discard her the next day. It’s a brazen show of confidence and remains as appropriate to modern fears of ghosting as it was to the early 1960s’ insistence on female chastity.

1970s

Marvin Gaye Let’s Get It On

A year after the publication of The Joy of Sex, Marvin Gaye released the perfect audio accompaniment to the illustrated manual that turned on a generation. In doing so he defined the template for sensual music. But for Gaye, Let’s Get It On wasn’t simply about pleasure, but liberation from his fundamentalist upbringing and abuse at the hands of his preacher father. For him, sexuality became spirituality. “I hope the music that I present here makes you lucky,” he wrote in the album’s liner notes.

1980s

Frankie Goes to Hollywood Relax

Taking its own advice, Relax took its sweet time creeping up the UK charts to eventually climax at No 1 in January 1984, by which point the BBC had already banned it for being too sexually explicit. Naturally, this did nothing to hurt its commercial prospects, and the band delighted in putting the Beeb in an awkward position when they repeatedly denied that it had anything to do with sex, gay or otherwise. The whole episode looks even more radical in retrospect, as a last hedonistic high before the Aids epidemic went mainstream.

1990s

Divinyls I Touch Myself

There had been songs about female masturbation before – notably Cyndi Lauper’s 1984 single, She Bop – but none as explicit or successful as this Top 10 hit from the Australian rock band. It’s not quite as progressive as it might seem, portraying self-love as a way of flattering a man’s ego; Tweet’s Oops (Oh My) would later better it as the singer gets turned on by the thought of a man, and then the sight of herself.

2000s

Peaches Fuck the Pain Away

“What else is in the teaches of Peaches?” Education, contraception, but above all, satisfaction. The Canadian electroclash artist’s breakout song fit perfectly into the easy sleaze of the new millennium, when strip-club culture penetrated pop and sex tapes started careers rather than wrecking them. Here, she added an essential seam of agency and sex-positivity.

0 Replies to “How Sex In Pop Has Changed Forever”